The Global Mobile Consumer Survey completed by Deloitte has revealed that 81 per cent of adults in the UK own a full touchscreen smartphone, with 91 per cent being between 18 and 44 years old. In addition, results have shown that smartphones are being used much less for traditional phone calls, rather, users are taking advantage of apps, such as social media, emails, or instant messaging.

|

| Credit: Deloitte.co.uk |

Smartphones are not only being used constantly and more often than other devices such as tablets or laptops, users are using them while engaged in other social activities, e.g. watching TV (81 per cent), having dinner (68 per cent), talking to friends (80 per cent) and others. Moreover, the survey has found that 52 per cent of its users uses their phone within 15 minutes and 86 per cent within an hour of waking up in the morning (Deloitte, 2016). There are many popular apps that are being increasingly used on smartphones, for example, WhatsApp with 1 billion active monthly users, or Facebook Messenger with 900 million (Statista, 2016).

|

Credit: Deloitte.co.uk

|

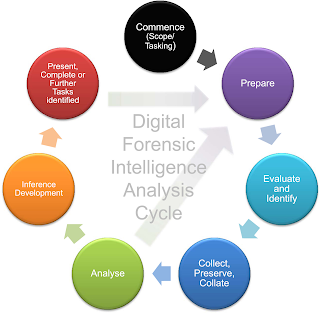

In today's world of growing organised crime and terrorism activity, it is important to be able to examine and process large volumes of data rapidly. By applying criminal intelligence analysis methodologies to digital forensic data extracts, there is a ‘potential to gain a greater understanding of mobile phone data, and contribute to a greater knowledge for tactical, operational, and strategic intelligence purposes’ (Quick, Choo, 2016). To form the Digital Forensic Intelligence Analysis Cycle, Quick and Choo merged steps from the Intelligence Analysis Cycle of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC 2011) and Digital Forensic Intelligence Analysis:

|

| Credit: Quick, Choo (2016) |

In this process, both the Intelligence Analysis Cycle, and the process of Digital Forensic Analysis are cyclical, it is an organic cycle during which analysts may uncover information relating to another mobile device, and return to a process of preparation, evaluation, identification, collection, preservation, and collation for the new device and its data (Quick, Choo 2016).

During organised crime investigations, large number of devices is likely to be analysed and different forensic methods would be required to extract data, and this could be a very time consuming process. A research has been conducted to find a generic method to export data and to determine if there is a ‘common export format which would enable the various extract types to be merged for intelligence and evidence analysis purposes’ (Quick, Choo, 2016).

The researchers examined different options to export data in

a variety of formats from ‘EnCase, FTK Imager, Cellebrite UFED, MSAB XRY, IEF,

Oxygen, and Paraben’. As a result, a volume reduction was observed, from a total of

339.9 GB to 207.6 MB in spreadsheets (CSV, XLS, or XLSX), and to 485.4 MB for XML

files, representing the exported and parsed data including contacts, calls,

messages, emails, Gmail, web bookmarks, GPS coordinates, and a range of other

application information’ (Quick, Choo, 2016). The combined spreadsheet data file was

then converted to Pajek data format and loaded into Pajek 64 software. A ‘Fruchterman

Reingold 2D entity link chart was created’, highlighting linkages of mobile

phone owners and their communication.

Further analysis then could assist in creating subject profiles of subjects within a possible organised crime network. The reduction of volume of data could benefit forensic intelligence analysts, as it becomes easier to manage, resulting in less time for processing, therefore speeding up the process of not only converting raw data into valuable intelligence, but also an overall investigation.

References:

Blondel, V.D., Decuyper, A. & Krings, G. (2015). A survey of results on mobile phone datasets analysis. EPJ Data Sci. (2015) 4: 10. DOI: 10.1140/epjds/s13688-015-0046-0.Further analysis then could assist in creating subject profiles of subjects within a possible organised crime network. The reduction of volume of data could benefit forensic intelligence analysts, as it becomes easier to manage, resulting in less time for processing, therefore speeding up the process of not only converting raw data into valuable intelligence, but also an overall investigation.

References:

Deloitte (2016). There’s no place like phone: Consumer usage patterns in the era of peak smartphone Global Mobile Consumer Survey 2016: UK Cut. Retrieved from https://www.deloitte.co.uk/mobileuk/assets/pdf/Deloitte-Mobile-Consumer-2016-There-is-no-place-like-phone.pdf.

Quick, D., Choo, K.R. (2016). Pervasive social networking forensics: Intelligence and evidence from mobile device extracts. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 86, 24-33.

Statista (2016). Most popular global mobile messenger apps as of April 2016, based on number of monthly active users (in millions). Retrieved from: http://www.statista.com/statistics/258749/most-popular-global-mobile-messenger-apps/.